Community-Led Responses to Conflict in the Sahel: Displaced Families Finding Refuge through Agroecology

In the face of rising food insecurity and displacement in the Sahel, a small town in Mali is leading a remarkable, women-led response to conflict—using agroecological practices to welcome and support Burkinabè refugees.

Dakuyo Izoun, a 55-year-old butcher from Doumbala, Burkina Faso, was forced to rebuild his life from scratch when armed groups attacked his village. As the country grapples with one of the world’s most neglected polycrisis, thousands are fleeing their homes in search of safety in neighboring countries. But even in the Sahel, one of the harshest environments on Earth, communities are finding ways to care for each other, building powerful models of solidarity and resilience while providing refuge for displaced families. Bankouma in Mali is one of them.

The Context of Displacement and Insecurity in the Sahel

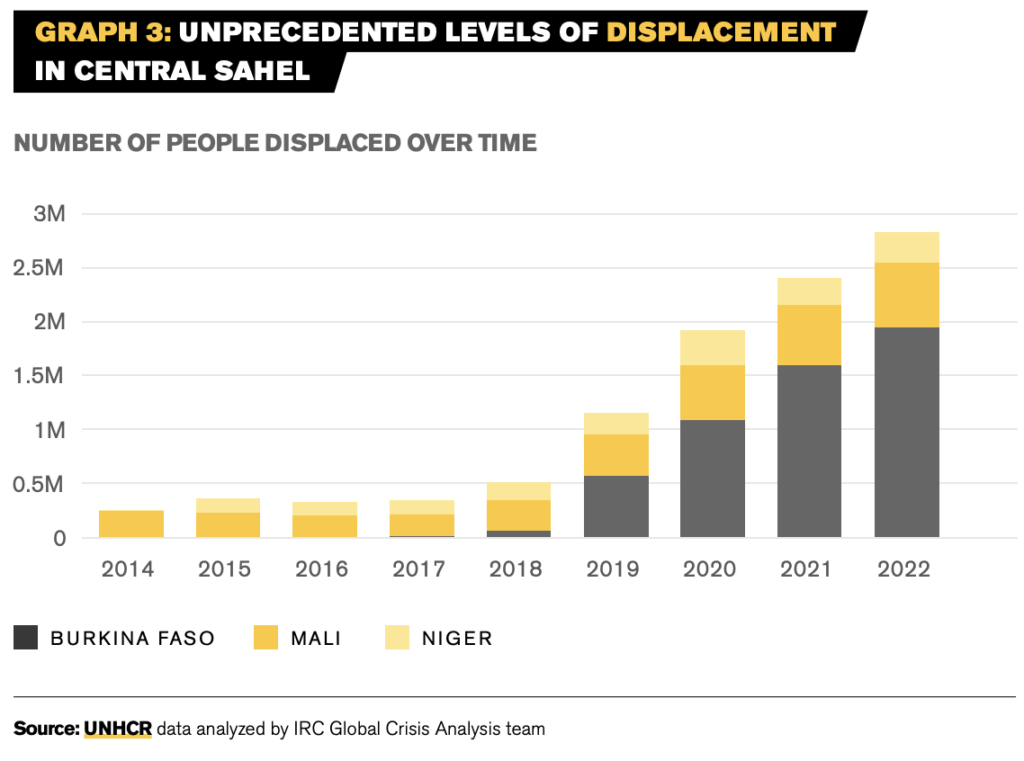

The Sahel region is facing unprecedented levels of food insecurity and displacement due to armed conflict and climate change, leading to many families fleeing their homes. By the end of 2023, about 3.3 million people had been forcibly displaced across Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger. This includes 2.8 million internally displaced individuals and over 500,000 refugees and asylum-seekers.

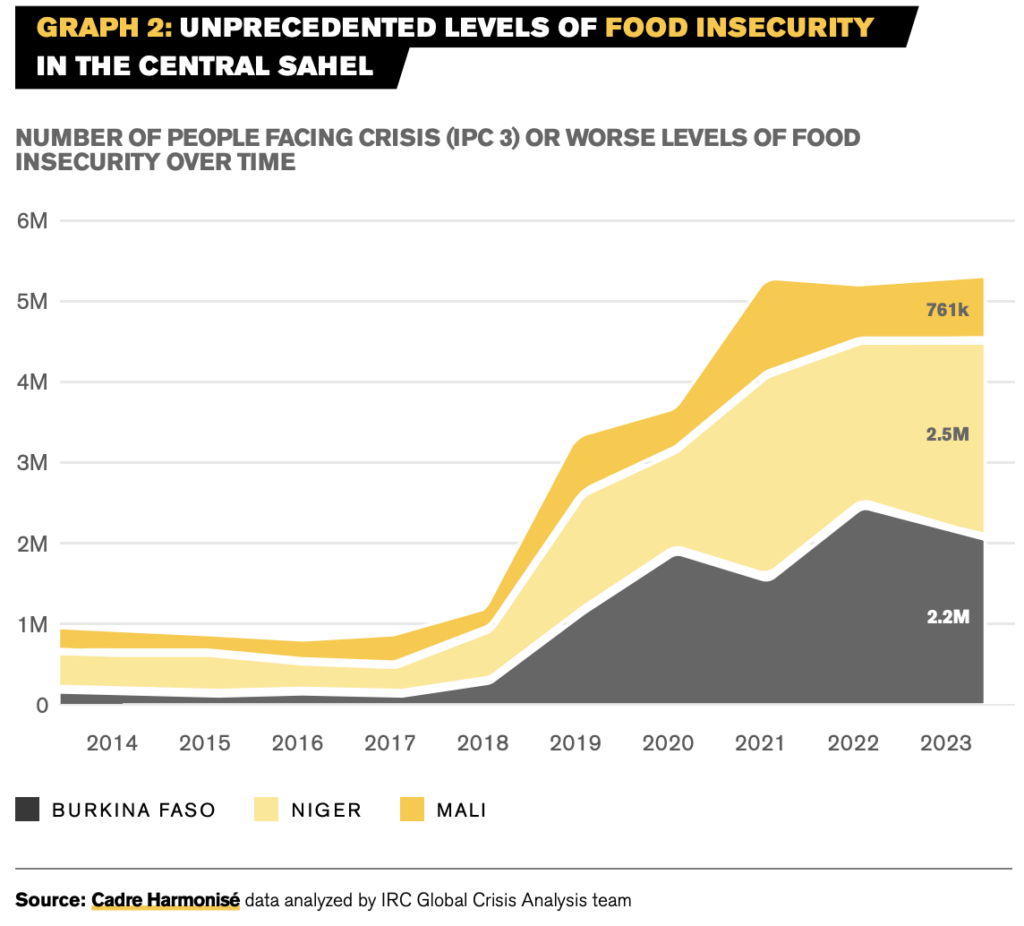

According to this IRC report (International Rescue Committee), food insecurity in the region has surged by a staggering 532% since 2014, while internal displacement has risen by an alarming 2,446%. This crisis is exacerbated by escalating terrorist violence, particularly in Burkina Faso and Mali, as armed groups affiliated with Al-Qa’ida and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara clash along the border. This ongoing conflict and inadequate support from international organizations and governments have left these nations among the most neglected crises in 2023.

As violence spreads, the humanitarian situation in the Sahel becomes even more critical. “Violence in the Sahel is not only fueling the food crisis, in many places it is instigating one” says Patrick Youssef, Africa Director for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Indeed, agriculture, the primary source of income and employment for over 80% of the Sahel’s population, is increasingly threatened. As violence forces families to flee their lands, crops are left untended, leading to severe yield losses. In Mali’s Liptako-Gourma tri-border region, over 80% of cultivable land across 100 villages has been abandoned, while post-harvest monitoring in Burkina Faso’s Yatenga and Loroum provinces shows yield losses of up to 90%.

In northern Burkina Faso, between 30% and 50% of land under cultivation has been lost to insecurity. The disruption of traditional transhumance routes – used by Mauritanian herders migrating with their livestock to Mali in search of pasture and water – has also jeopardized livelihoods, as these routes become too dangerous to navigate.

When populations are forced to abandon their land, they lose their primary means of survival, becoming reliant on external aid for food and water, urging for sustainable local solutions that complement emergency relief.

And climate change further compounds these challenges. According to the United Nations, temperatures in the Sahel are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average, significantly affecting agricultural activities. Frequent droughts are intensifying arid conditions, making land increasingly barren and challenging for crop production. The region is experiencing the worst drought in decades, with rainfall levels comparable to the catastrophic drought of 2011, which led to thousands of deaths. The situation for millions of families is dire and expected to worsen in the coming months, urging for efficient, widespread local and international conflict support.

A New Beginning in Bankouma, Mali

Against all odds, a village in the Ségou Region of Mali has managed to escape – or brilliantly adapt – to this polycrisis. Situated close to Mandiakuy within the Tominian Cercle, with a diverse population of various ethnic groups such as the Bambara and the Bobo, Bankouma is a subsistent agricultural village cultivating common crops like millet, sorghum, maize, peanuts, and vegetables. Lack of water, degrading land and declining access to resources are daily challenges, and the region isn’t spared by rising violence. But a local NGO called Sahel Eco is transforming this town into a refuge for the people of the Sahel, especially displaced families.

When Dakuyo arrived in Bankouma with about 200 other refugees from Burkina Faso, they were welcomed with open arms. Some didn’t know the local language. Others lacked agricultural knowledge. Yet, despite their fair share of challenges, the people of Bankouma shared their resources and homes with their displaced neighbors, offering them a chance to rebuild their lives in a safe, supportive environment.

But this outpouring of solidarity would likely not have happened without the Market Garden Project, which has become central to the well-being of the Bankouma community and their capacity to welcome displaced families.

The Market Garden Project: a local, sustainable response to the food and conflict crisis in the Sahel

Developed by Sahel Eco in partnership with local women farmers, the project addresses food security, promotes community integration, and nurtures sustainable livelihoods through agroecological practices. By increasing access to land and water, and focusing on capacity-building, it equips locals and displaced families with tools for self-sufficiency.

The project, officially titled Strengthening the Resilience of Women Market Gardeners to Curb the Impact of Climate Change, primarily targets women and refugees. Participants grow chemical-free vegetables on a one-hectare plot, improving household nutrition while supporting their livelihoods.

Led by Dibihan Ruth Diarra, a respected local farmer, the project involves 65 farmers, 73% of whom are women. Under Dibihan’s leadership, participants learn to make compost and bio-pesticides, ensuring healthy crops while restoring the land. Her expertise in agroecological practices has ensured the garden’s productivity while building a supportive and collaborative environment among men and women farmers. Many in her group look up to her for daily solutions and counsel on farming techniques.

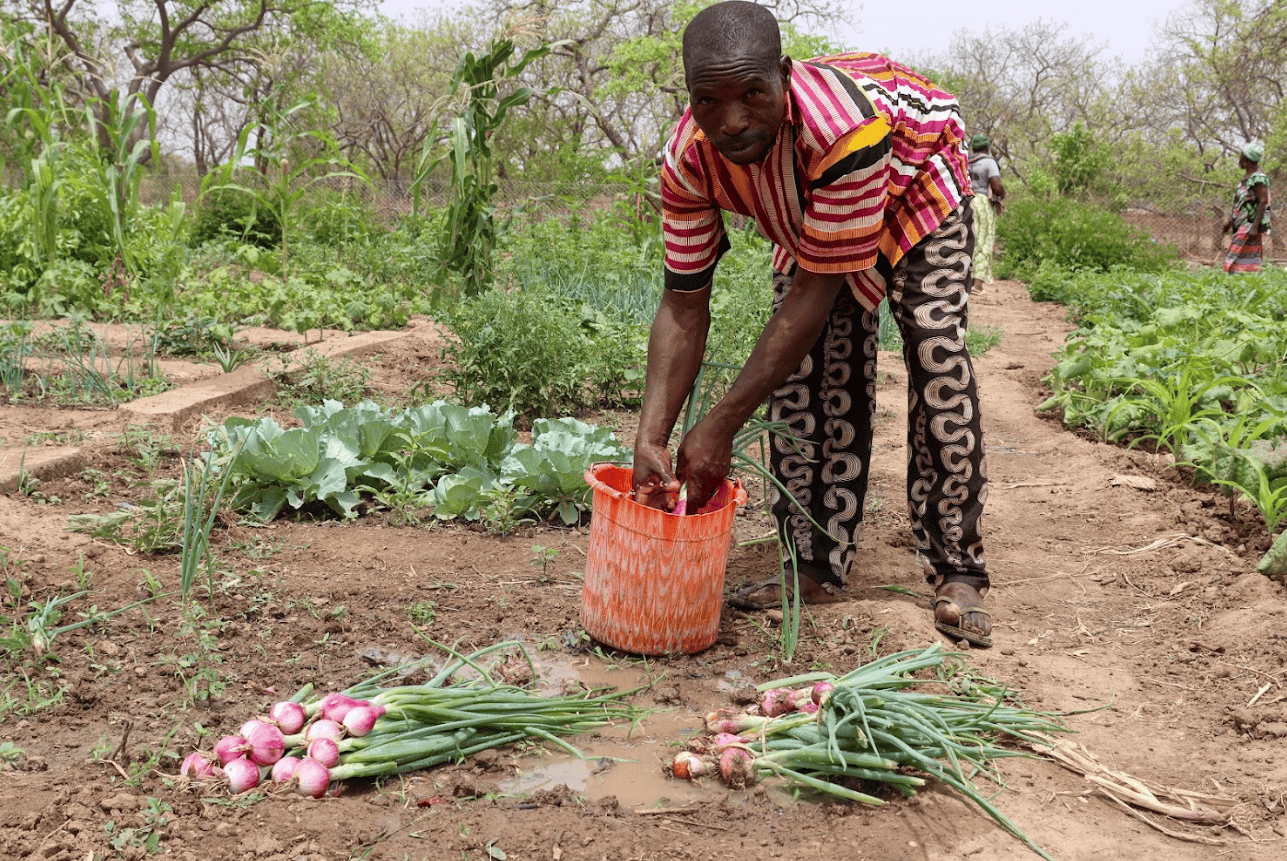

For refugees, the project is a lifeline. Instead of being isolated from the locals, Dakuyo received a plot where he cultivates onions, okra, and beans. From butcher to farmer, he now plays an active role in enhancing the community’s well-being and has regained a sense of purpose. He reflects, “Working the land has allowed me to keep my dignity and preserve the unity of my family.” This integration ensures that displaced families, like Dakuyo’s, are active contributors to the community.

The Market Garden Project focuses on three key objectives:

- Food security: The garden’s produce reduces dependence on external aid, meeting the nutritional needs of both locals and refugees. In a region where international aid has been cut off for many people, due to main transport routes becoming inaccessible to the IRC and other aid organizations because of armed groups, local, autonomous and healthy food production and access is vital. The project helps improve nutrition, leading to healthier and more resilient families.

- Economic stability: Selling surplus crops at local markets provides income for families, helping them regain financial independence. Refugees had to leave everything behind when fleeing their homes, and many depended on their land to survive. Without access to their land, they lose their main source of income. The project gives them another chance at life by regaining access to key resources, such as land, tools, and water. With this new income, families can pay for school fees and other essential needs without depending on external assistance.

- Dignity and integration: By working the land, refugees not only earn a living but also rebuild their sense of purpose, facilitating their integration into the community.

Market gardening has become a lifeline for women in Bankouma and displaced families alike, improving nutrition, generating income, and offering a path to self-reliance.

“Working the land has allowed me to keep my dignity and preserve the unity of my family.“

Dakuyo Izuon, a Burkinabè refugee who became a farmer after integrating the Bankouma community in Mali

Community-led solutions on the frontline

Bankouma exemplifies the countless instances where communities lead in crisis response, highlighting their indispensable role in facing escalating migration challenges linked to conflict and climate change.

When a devastating earthquake hit Haiti in 2010, killing over 200,000 people and displacing 1.5 million others, rural communities opened their arms to welcome and care for victims. Similarly, when Beirut was struck by a massive explosion in 2018, leaving 300,000 people homeless with inexistent support from the government, Lebanese from all walks of life united in solidarity, forming grassroots initiatives to clean up debris, distribute supplies, and care for the injured. In Gaza, amidst the rubble and despair, community bonds are crucial for finding moments of joy and support.

These instances of hardship demonstrate that communities often provide the most immediate and practical support in times of crisis. While organizations and governments play important roles, those who have experienced similar challenges firsthand extend the first and often most meaningful helping hand.

The resilience and solidarity exhibited by local communities in the Sahel, Haiti, Lebanon, Gaza, and many other places remind us of the enduring strength of collective action and compassion during adversity. This is why we prioritize community-led approaches like agroecology in our work: we do not do it for communities – we equip them with the tools and support they identify as essential to reaching their collective goals, building on their existing strengths and values.

Agroecology as a response to conflict in the Sahel: a scalable solution

The success of the Bankouma Market Garden Project offers valuable lessons for other parts of the Sahel region. Like Sahel Eco’s work, Groundswell International’s partners in different countries in the West African Sub-Region—Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Senegal—each implement their versions of the Market Garden Project for marginalized communities. To learn more about their work, read this report showcasing how agroecology and supportive social measures helped build resilience in the Sahel.

These efforts demonstrate that with the right support and agroecological approach, displaced communities can move towards food security and economic stability. This model is replicable, offering a sustainable solution to displacement and food insecurity, while reducing dependence on external aid, especially in neglected countries like Mali and Burkina Faso.

As Patrick Youssef, Africa Director for the ICRC, stated in this article: “While it is imperative to respond to this crisis (in the Sahel), simply thinking in terms of emergency will keep people reliant on assistance and the cycle of suffering will repeat itself. (…) Development actors, governments and humanitarian organizations must come together and put forward new and innovative solutions that will reinforce existing systems and provide tools that will help people break their dependence on aid.” The Market Garden project can inspire the creation of such solutions.

Support community resilience in the Sahel

Despite the successes of the Market Garden Project, water scarcity remains a significant challenge in Bankouma. Dibihan emphasizes the urgent need to increase water levels within the garden perimeter to sustain and expand their efforts.

Both Dibihan and Dakuyo need your help to secure additional water resources, essential for maintaining this vital initiative and supporting the displaced families who depend on it. Your contribution will help expand critical projects in the Sahel and ensure food security and access to clean water.

About our local partner Sahel Eco

Sahel Eco, founded in 2004, works with the people of Mali to improve their livelihoods through better environmental management. They support rural communities in the Mopti and Segou regions and has greatly influenced the policies and practices of both government and peer agencies to promote farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) within a broader regional “re-greening movement.”

The NGO runs various agroecological projects, such as disseminating seedlings to farms to support reforestation and re-greening efforts and holding farmer field schools to encourage farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchanges and skill building. In 2023, Sahel Eco began participating in rainwater management projects to help farmers adapt to low and erratic rainfall patterns in the Sahel.

Learn More: www.saheleco.org

This article was written by Maylis Moubarak and Freda Aagyereyir Pigru. Meet our staff.