Communities Strengthening Food Sovereignty in Central America with Seed Banks and Strategic Grain Reserves

This article was originally published in Spanish. Read it here.

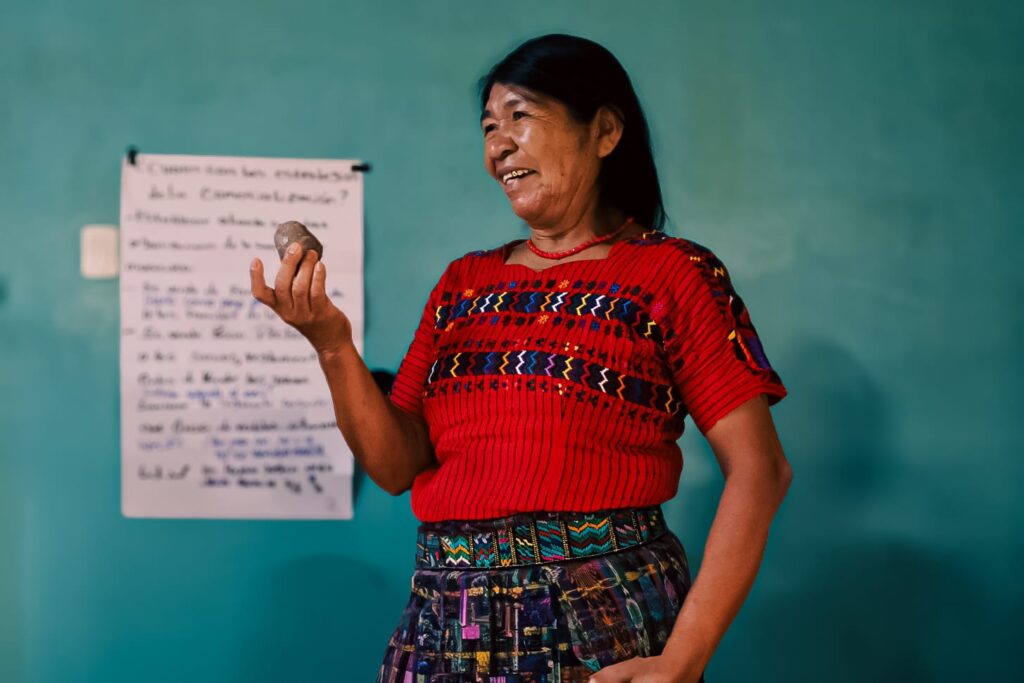

For a week, representatives from communities in Guatemala and Honduras gathered at the Association of Ecological Committees of Southern Honduras (ACESH) offices to share knowledge on grain storage, seed conservation, and strategies for food sovereignty. Farmers, community coordinators, and technicians from our partners Qachuu Aloom, Vecinos Honduras, the Association of Farmers Las Ilusiones del Divisadero (AGRIDIVI), and ACESH exchanged strategies and experiences that have transformed food production and supply in their territories. Each community brought a legacy of practices that have sustained generations, now facing challenges due to climate change, economic pressures, and the loss of arable land.

Strategic grain reserves as a response to uncertainty

Strategic grain reserves can be a key response to climate uncertainty and economic fluctuations. ACESH, an organization committed to the sustainable management of natural resources in southern Honduras, has worked with 32 communities to establish grain reserves using plastic bags, repurposed bottles, or clay silos for storage.

In Guatemala, Qachuu Aloom, an organization dedicated to preserving ancestral knowledge and promoting food sovereignty with a focus on gender equity and cultural identity, has also embraced various methods for seed conservation. In Baja Verapaz, they store seeds in airtight clay containers kept in a cool room, arranged on shelves, or buried underground, creating a small laboratory to study the best long-term preservation methods.

Each storage method is adapted to the community’s local context. Plastic bottles and bags help prevent moisture, while clay silos offer a more sustainable and higher-capacity solution. These reserves guarantee food security in times of scarcity and serve as a buffer against price speculation in external markets, protecting families from fluctuations in the cost of staple foods like corn and beans.

Seed preservation was a central topic of discussion during the exchange. In AGRIDIVI, a Guatemalan farmers’ association dedicated to conserving native seeds and strengthening agroecology, various preservation methods are used, such as storing seeds in glass jars with garlic and chilies as natural repellents or covering them with ash to extend their shelf life.

In other communities, organized groups are responsible for selecting and safeguarding seeds, preventing the disappearance of native varieties, and ensuring their continuity for future harvests. The introduction of hybrid varieties has raised concerns about the loss of traditional seeds, prompting some communities to establish seed banks where they exchange and document seed characteristics for long-term conservation.

Local markets and community-based trade

Local and community markets have become another strategy for ensuring food accessibility. These markets allow farmers to sell corn, beans, and processed foods such as tortillas and atole. The frequency of these markets varies by community—some hold them monthly, while others organize them more frequently depending on harvest cycles.

These markets have also revived barter systems, enabling families to access essential foods by trading goods or services. Beyond generating income, these exchanges strengthen local networks and provide direct access to food without reliance on large distribution chains, reinforcing circular economies within communities.

Learning from successful community initiatives

During the gathering, participants visited communities that have successfully implemented some of these strategies or are developing new initiatives to strengthen their territories through agroecology.

In La Cabañita, for example, a grain reserve and a loan system have been established to help farmers purchase fertilizers and medicine. This community has struggled with youth migration, reducing the number of active farmers. To counteract this, they have launched training programs and access to credit to encourage young people to stay in agriculture.

In El Muñeco, each family contributes one quintal (100 kg) of grain per year to maintain a collective reserve used during times of scarcity. The community has also implemented a savings system with adjusted interest rates, improving access to financial resources and creating emergency funds for urgent agricultural or community needs.

Land access and community organizing

Land access was a recurring issue expressed by communities. Land concentration in Central America has restricted agricultural production and made it harder for families to remain on their land. Some communities have tried to purchase land collectively, but lack of financing and property titles remain significant barriers.

Another pressing issue is the impact of extractive projects, which have displaced communities and reduced the availability of farmland. In response, some communities have pursued legal organization and collective land titles to protect their territories.

The role of youth in strengthening local agriculture

Youth involvement in food production and community management emerged as a crucial strategy for resilience. Vecinos Honduras, which supports food sovereignty and community development in rural areas, has worked to engage younger generations through entrepreneurship workshops, audiovisual production, and digital tools to share knowledge and experiences.

Additionally, they developed mentorship programs where experienced farmers teach young people about agricultural practices, seed management, and resource administration. These efforts aim to strengthen ties to the land and offer alternatives to migration by creating viable futures in rural areas.

Challenges and collective solutions

The gathering also addressed external agricultural production challenges, such as mining operations and unreliable electricity supply. In some regions, mining activities have contaminated water sources and soil, endangering crops. Frequent power outages have disrupted food preservation and daily activities, affecting irrigation systems and refrigeration of perishable products.

To counteract these challenges, communities have strengthened their cooperative networks and adopted agroecological practices to reduce dependence on external inputs. They explored solutions like solar-powered irrigation systems and rainwater harvesting to cope with droughts.

Beyond sharing food production and storage strategies, the exchange helped strengthen community coordination. Cooperation has proven essential in improving food security in a context shaped by climate and economic crises. As a result, communities have agreed to establish permanent communication networks to share progress and challenges, ensuring that the strategies discussed continue evolving and adapting to the changing conditions of each territory.

These efforts need your support to continue growing. Here’s how you can help: share these experiences so that more people know the value of seeds and peasant work, and donate so that communities have access to more tools, resources and exchange networks. Every contribution strengthens the path towards fair and self-sufficient food production, where decisions are made by the same hands that cultivate the land.

About the author

Luisa María Castaño Hernández

Luisa María Castaño Hernández is Groundswell International’s Communications Coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean. She has experience in media in different countries, content development in multimedia and print formats, fiction and non-fiction writing and editing. She has played a leading role in the formulation and implementation of communication strategies for projects of institutions working for the preservation of cultural heritage and biodiversity, the strengthening of education and the integration of migrants. She has also participated in the development of museographic scenarios, curating exhibition cycles and educational experiences in art and science museums. She is a journalist, artist, and has a Masters in Humanistic Studies.